Harveys Casino Lake Tahoe Bombing

Here is a video snippet of a bomb that was detonated in Harvey's Casino in Stateline, Nevada - next to South Lake Tahoe, California. The bomb consisted of ov. Terry Lee Hall registered at the Balahoe Motel, on Emerald Bay Road just north of the Lake Tahoe Airport, on Aug. 25, 1980, the day before the bomb was delivered to Harvey's Resort Hotel. Harvey’s had 24 hours to act. “Any deviation from these conditions will leave your casino in shambles,” the bombers warned. For the next three days, the normally bustling casino district of Lake Tahoe was shut down as bomb experts from around the country tried to disable the device and authorities tried to meet the extortionists’ demands. Tahoe's Big Bang In the summer of 1980, Harvey's Resort Hotel and Casino, along the California border in Stateline, Nevada, became the site of the largest domestic bombing in U.S. It would continue to hold that distinction for more than a decade, until the bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993.

Joseph Yablonsky, special agent in charge of the FBI's Las Vegas office, holds up a photo of the bomb taken by Douglas County sheriff's deputies after it had been dusted for fingerprints.

Photo: The Associated PressSandbags were trucked in to lessen the impact of the blast.

Photo: Tahoe Daily TribuneThe Douglas County Sheriff's Office dusted the bomb for fingerprints and collected other forensic evidence before the bomb squad attempted to disarm it. Photo: FBI / Tahoe Douglas Bomb Squad

Photo: FBI / Tahoe Douglas Bomb SquadJohn Birges was convicted in 1981 of masterminding the extortion attempt at Harveys the previous year. He died in prison in September 1996.

Photo: Tahoe Daily TribuneAfter the casino corridor was evacuated, technicians detonated a bomb left in Harveys along with an extortion note.

Photo: FBI / Webb CanepaLake Tahoe police and El Dorado County sheriff's deputies keep the crowd of onlookers off of Highway 50 after the detonation of the bomb at Harveys in August 1980.

Photo: The Associated Press

Photo: FBI / Tahoe Douglas Bomb Squad

John Birges. A former steel worker and landscaping contractor, Birges designed and build the bomb and masterminded the $3 million extortion plot.

Photo: FBI

Harveys Casino Lake Tahoe Bombing Victims

The letter next to the fake copy machine at Harvey’s Resort Hotel on Aug. 26, 1980, started with a warning.

“Do not move or tilt this bomb, because the mechanism controlling the detonators in it will set it off at a movement of less than .01 of the open end Ricter scale.”

A bomb threat in Tahoe’s casino district was not unchartered territory in 1980. The marriage of money, booze, hope and loss would occasionally birth a third-rate extortion attempt that almost always ended with the discovery of a fake device or no bomb at all. But investigators would soon learn the 1,200-pound device on the second floor of Harvey’s — where about 600 people were staying ahead of Labor Day weekend — was anything but third-rate.

“I just remember looking at that and thinking, ‘my gosh this is the biggest thing that I had ever seen,’” said Bill Jonkey, a then FBI special agent based in Carson City who was first on the scene for the Bureau.

It was the beginning of a failed shakedown that triggered the most intense 35-hour period in Tahoe’s modern history, thrusting Stateline into the national media spotlight and forever altering how law enforcement dealt with threats of improvised explosives. No lives were lost, but the blast blew a chasm through the building and initiated a year-long investigation that ended with the arrest of the bomb maker and his accomplices.

The Harvey’s Resort bombing was considered the largest domestic bombing in the U.S. until the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, which would later be out-shadowed by the deadly Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. The successful outcome — as deemed by Jonkey and others involved — of the tense 35-hour period was a product of collaboration mixed with a hint of what so many people hoped to find in Tahoe: luck.

IS IT REAL?

Employees at the casino and hotel built by Harvey Gross were the first to discover the device in the early morning hours of Aug. 26. Men sporting white jumpsuits wheeled what, according to the FBI, appeared to be an IBM copy machine onto the second floor of the casino where the executive offices were housed.

In addition to the direct warning and ensuing explanation of the bomb’s complexity, the three-page letter included a demand: $3 million in used $100 bills.

“I repeat do not try to move, disarm, or enter this bomb. It will explode.”

Security guards initiated an evacuation of the casino and hotel for what they described as “a serious security problem,” according to a story published in the Tahoe Daily Tribune 10 years later. For some guests, the lack of information and direction fueled a frightful experience.

“No one told us where to go, what to do,” Stockton resident and hotel guest Marjorie McComb told the newspaper. “It was frightening. We didn’t know what to do.”

Ron Pierini had recently been promoted to the rank of captain in the Douglas County Sheriff’s Office. He was a station commander at the lake and was at home that morning when he got the call.

“You wonder if it’s really a bomb or what is it,” Pierini recalled.

It did not take long to determine that the bomb was not an empty threat.

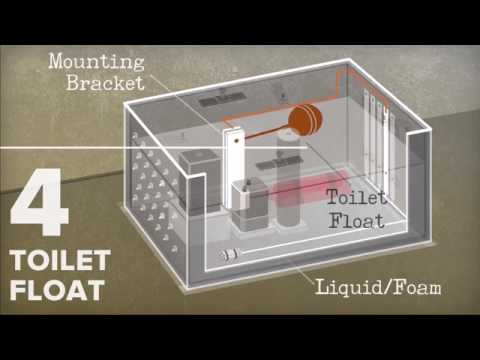

The intricate details described in the letter signaled to investigators that they were not dealing with a spontaneous swindler. The letter claimed that the bomb had at least eight triggering mechanisms that would prevent it from being moved or taken apart — a float switch and an atmospheric pressure switch were both attached to detonators, as were the flathead screws binding the containers shut. It could never be disarmed without triggering an explosion. And there was enough TNT inside to damage neighboring Harrah’s Casino across U.S. 50, the letter claimed.

“There was shock and awe just as to the size of it and as to the apparent degree of sophistication,” Jonkey said.

Photos and X-rays confirmed the bomb, made of two steel boxes underneath the cloth copy machine disguise, contained about 1,000 pounds of dynamite. Law enforcement initiated a multi-pronged response to secure the area, eliminate the threat of explosion and catch the bomb maker.

BOTCHED RANSOM

The bomber’s letter left detailed instructions for delivering the $3 million. It was to occur at night via helicopter. An unarmed pilot was to park by the Lake Tahoe Airport building at 11 p.m. and wait for instructions to come by taxi or a nearby pay phone.

The bomber set conditions. The news media was to be kept in the dark about the transaction. The pilot was to be alone and unmonitored — failure to comply could result in the unnecessary taking of lives. The helicopter was to be fully fueled.

Harveys Casino Lake Tahoe Bombing Map

“The extent of your co-operation will make the difference. If you co-operate fully it will insure a very speedy exchange. We don’t want to burden your business opportunities or cause more loss of money than is necessary.”

Once the money was received there would be a progression of instructions for neutralizing specific triggers, which would allow the bomb to be removed from the casino and detonated at a safe location. Those instructions proved moot because the transaction never occurred. After receiving the initial instructions via the pay phone, the helicopter pilot couldn’t find the people at the supposed drop site off U.S. 50 west of Echo Summit, Pierini recalled.

Even if the exchange had occurred, the extortionist would have been disappointed. Leading up to the decision, the FBI informed Gross that the device, which weighed roughly 1,200 pounds, would almost assuredly blow or be completely disarmed inside the casino. Gross, whose primary concern was making sure nobody was hurt by the blast, made it clear he was not paying the ransom.

“He said, ‘no.’ He wasn’t going to pay them a dime,” Jonkey recalled of his conversation with Gross.

EXPLOSIVE ATTRACTION

The task of clearing the scene fell largely to local law enforcement at first. The hotel guests were herded onto buses and taken to George Whittell High School and Zephyr Cove. Authorities attempted to move as many cars from the Harvey’s parking lot as possible, though some remained. Plywood was placed in some windows to protect against what increasingly seemed to be an inevitable blast.

Despite some reports that the neighboring casinos — at the time they were Harrah’s, the Sahara (now Hard Rock Lake Tahoe) and Caesars (now Montbleu Resort Casino and Spa) — Pierini said they largely forced the gamblers and guests in the other casinos to move away from the parts of the businesses closest to Harvey’s.

“They were still playing 21 when it went off,” recalled Pierini, who went on to serve as Douglas County sheriff for many years before retiring in January 2019.

In a brief video recounting the ordeal, retired FBI Special Agent Chris Ronay recalled how the bookmakers in the other casinos started taking bets on if and when the bomb would go off.

“I mean the casinos set up the gambling procedures on this event,” Ronay said in the video.

Hordes of curious people gathered at the various roadblocks and barriers and watched with anticipation. The bomb threat had become Big Blue’s biggest attraction.

Despite the influx of national media and law enforcement and the presence of end-of-summer revelers, law enforcement was able to keep the mass of people out of harm’s way.

But it couldn’t hold the line forever.

“That was one of the concerns we had… we just didn’t think we could contain that perimeter a whole lot longer,” Jonkey said.

SAFEST BET

As the hours ticked by, explosives experts hatched what was deemed the best plan for disarming the bomb. It involved separating the top steel box, which contained the switches, from the bottom box, which contained most of the dynamite. If the boxes and wiring could be severed almost instantaneously, the theory went, it might prevent the charge from reaching the explosive material.

Those involved agreed it was the best chance at the time, but it still carried a high probability of failure. Then-Douglas County Sheriff Jerry Maple told the Tahoe Daily Tribune that there was a 25-30% chance the plan would work. In consulting with an engineer from Harvey’s, officials determined that full detonation likely would not bring down the entire building.

On Aug. 27, nearly 35 hours after the bomb had been discovered, Tahoe Douglas Bomb Squad Capt. Danny Danihel made his way toward the bomb alone. He placed the charge used to separate the boxes and exited the building.

Jonkey surveyed the scene from atop the Sahara. The countdown commenced over the radios. Hopes of successfully disarming the bomb evaporated with a loud boom followed by a cloud of debris that spread outward over U.S. 50, then upward.

“You could feel the explosive wave,” Jonkey said.

“Right after the explosion, we realized we had one hell of a bombing crime scene to deal with.”

REOPENING AND REBUILDING

The blast transformed Tahoe’s oldest casino into a scene resembling a war zone. The sheer power of the bomb blew a five-story fissure through the 11-story building, according to the FBI. Cement and fixtures hung from twisted rebar. Debris, including gaming chips and money, littered the area.

“There was money everywhere,” Pierini remembered.

The National Guard worked with law enforcement and Harvey’s security staff to gather all the chips and money as investigators analyzed the scene. Media reports claimed that every dollar was ultimately accounted for, though that did not stop the claims from Harvey’s guests who argued possessions were missing from their evacuated hotel rooms.

While zero people were killed, the damage to the building was a gut punch for Gross — a man described in a New York Times obituary three years later as “a gambling pioneer” who turned a club with six slot machines after World War II “into a multimillion-dollar casino empire.”

“He started crying and he said, ‘thank God we didn’t hurt anyone,’” Pierini said of Gross as he surveyed the wreckage.

“Harvey was a great guy, and he just put all his effort into that position. It was tough for him.”

The total cost of the damage was estimated to be around $18 million, according to the Tahoe Daily Tribune story published around the 10th anniversary of the bombing. Although the damage was significant, it didn’t take long for the gamblers to return. The same Tribune story notes that part of Harvey’s reopened 48 hours after the blast.

“They went back to gambling pretty damn quick,” Jonkey said with a laugh.

Ronay, the retired FBI special agent interviewed on video about the incident, said a temporary wall was erected and a window was installed so people could view the blast scene where the investigation continued for weeks.

In May 1981, the fully renovated and repaired Harvey’s reopened to the public. At the ribbon cutting, Gross boasted having “the most modern fire and safety devices available in the hotel industry,” according to Tahoe Daily Tribune archives. The new Harvey’s employed about 3,000 people at the time. Nearly five years later, Harvey’s opened a new 18-story, $100 million hotel tower.

ARREST AND REFLECTION

Nearly one year to the day of the bombing, authorities arrested John Birges Sr., the builder of the bomb. Born in Hungary in 1922, Birges immigrated to the U.S. in 1957 and founded a landscaping company in Fresno, according to Tahoe Daily Tribune archives. The company made him a millionaire, which fueled his gambling addiction. Though the exact figure varies depending on the account, Birges Sr. is believed to have lost at least $750,000 gambling at Harvey’s over the years.

Birges’ two sons, John Jr. and Jimmy, played a role in the extortion attempt, as did his then girlfriend, Ella Joan Williams. Two laborers hired to place the bomb in the casino, Willis Brown and Terry Hall, were also charged in the case. Birges Sr. died of liver cancer on Aug. 27, 1996, in the Southern Nevada Correctional Center.

Though the disgruntled gambler has faded from the consciences of all but those connected to the bombing, the legacy of the event lives on. The device is still regarded by the FBI as one of the most unique improvised explosive devices in the Bureau’s history. It transformed how agencies respond to bomb threats. Jonkey and others would later assist in the tragedy that occurred in Oklahoma City. The Harvey’s bombing also changed casino operations in the U.S.

“I think they became far more diligent in their observations … the casino industry in general hardened their protocols to prevent another thing like that,” Jonkey observed.

Looking back nearly 40 years later, both he and Pierini credit the successful outcome to the collaboration among the various stakeholders. Every agency played a role, and those involved didn’t let egos complicate the response.

Still, minor details in the larger story contributed as much as anything else in the overall outcome. As Pierini noted, had one of the employees attempted to move the device in the very beginning — an entirely plausible development — the site on the California-Nevada border could have been one of unfathomable carnage and tragedy.

“I think we were lucky,” Pierini remarked.

“It could have been a lot worse.”